Digital wallets enable essential applications like encrypted messaging and online banking. However, digital wallets are vulnerable to loss and theft. In this paper, we investigate current wallet standards. We show that multi-signature wallets are an insufficient replacement for classical hierarchical deterministic keychains. We address the usability concern of multi-signature wallets with threshold cryptography. SWORD improves the security of digital wallets by distributing account management across a group of shareholders. In addition to removing a single point of failure, SWORD simplifies the wallet experience by incorporating passwordless authentication. SWORD has been adopted and is used in the open-source Kryptik wallet.

1. Introduction

The internet relies on a peer-to-peer connection between computers, but the majority of services we use daily are centralized. While corporations like Chase and Facebook are easy to use, centralized convenience often comes at the cost of privacy and ownership.

Since the development of Bitcoin in 2009, there has been a significant push to make the internet more decentralized. Blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum promise to shift power from the few to the many, opening a new frontier of digital exploration.

A few examples of popular blockchain apps are shown below.

- Augur. A prediction market for betting on real world events like sports games and election outcomes.

- Opensea. A marketplace for digital collectibles.

- Lens. A user controlled social media platform. Developers can use a standard interface.

- AAVE. Lending and borrowing with over four billion dollars in assets.

- SIWE. One click login using an Ethereum account.

- Uniswap. A decentralized exchange for digital currencies.

- IPFS. Store files on a global network of computers.

Every blockchain application requires a digital wallet that can send and sign transactions. Since 2009, over one hundred million wallets have been created worldwide.

2. Wallets Are Hard to protect

One of the best parts of cryptocurrency wallets is the ability to control your own money and data. Unlike traditional banks or third-party services, no third party holds assets on your behalf. However, with great power comes great responsibility.

Over $85,000,000,000 worth of cryptocurrency has been permanently lost after users have lost access to their wallets.1

Today, holding your own cryptographic keys requires memorizing long mnemonic phrases, trusting third-party custodians, or purchasing complicated hardware wallets. These solutions are insufficient for most internet users looking for a simple way to manage private keys.

3. Standard Solutions

Noncustodial wallet management is an open problem, with an inherent tradeoff between security and ease of use. Standard solutions are shown below:

Multisig Wallets. A multi-signature wallet requires multiple private keys to authorize transactions.

Smart Contract Wallets. Smart contract wallets are just a multisig with extra bells and whistles for recovery and permissions. For example, Argent— a smart contract wallet with over four million accounts— allows ‘guardians’ to replace the account owner and set approvals for value-subtracting transactions.2

Account Abstraction. Account abstraction turns every blockchain account into a smart contract wallet.3 Account abstraction has not been implemented on major blockchains like Ethereum despite discussion since 2014.

Smart contract wallets have been described as a breakthrough in the security and usability of crypto wallets; However, smart contracts have significant drawbacks, explained below:

- Network Specific. Smart contract wallets are implemented as code that runs on a single blockchain. Chain-specific contracts require users to create a separate wallet for each blockchain which is a hassle and a security risk.

- Time Lag. Adding guardians or transferring ownership requires a ‘security period’ that can last multiple days. No UTXO support. Smart contract wallets require Turing-complete blockchains, so there is no support for transaction-based networks like Bitcoin.

- Variable fees. Processing payments requires executing smart contract code, which can vary in cost for each wallet.

- Upfront cost. Smart contract wallets require an initial setup fee to pay for the creation of a new contract on the blockchain.

Large companies may benefit from the policies provided by smart contract wallets. However, smart contracts restrict wallets to a single blockchain and prevent users from accessing the benefits provided by a unique public-private key pair.

Multi-party computation (MPC). MPC wallets require multiple participants to authorize a transaction. Unlike multi-signature wallets, MPC wallets submit a single signature to the blockchain, reducing transaction fees and enabling interoperability with multiple blockchains. However, multi-party computation protocols have high computation and communication requirements. The industry standard requires four rounds of online computation or seven rounds of pre-signing computation.4 In addition, most user-facing implementations like Coinbase dApp Wallet and Zengo allow a single computer to initiate a signing round.5

MPC wallets are best suited for institutions that can maintain multiple independent signers.

Multi-party computation also encourages walled gardens. Users are limited to the provider’s ecosystem without access to the wallet seed.

4. Wallet Basics

Random Seeds. At the core of every wallet is a single seed: a string of randomness. As a seed grows in length, the less likely it is to be guessed by an attacker.

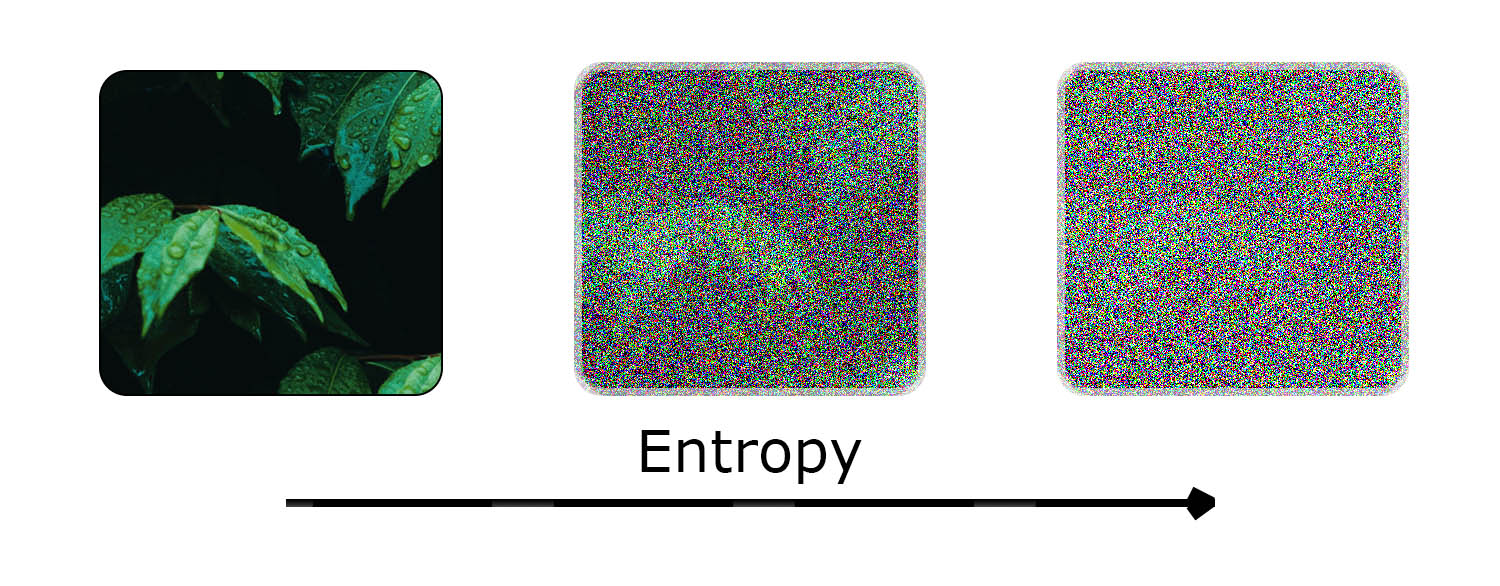

Most wallets use seeds with 256 bits of entropy. In practice, this looks like a long string of ones and zeros, with each character having two distinct possibilities. The number of possible seeds grows exponentially. For example, if a seed has 8 bits of entropy, there are 28 (256) possibilities of what it could be. With 256 bits of entropy, there are 2^256 possible seeds, which is more than the number of atoms in the observable universe.

| Entropy As an Image |

|---|

|

| Entropy is a measure of randomness. The more entropy increases, the less likely a piece of information can be guessed. |

Seeds are hard to guess and are an ideal source for generating public-private key pairs.

Deterministic Wallets. Early Bitcoin clients used a random stash of keys once per transaction. Once the initial supply of keys was exhausted, wallets would invalidate the backup; this made key management complex and insecure.6

Deterministic wallets simplify key management. A single seed can generate an unlimited number of keys. However, most deterministic wallets store keypairs on a single chain. Sharing a deterministic wallet is “all or nothing”: sharing a single key requires sharing all keys.

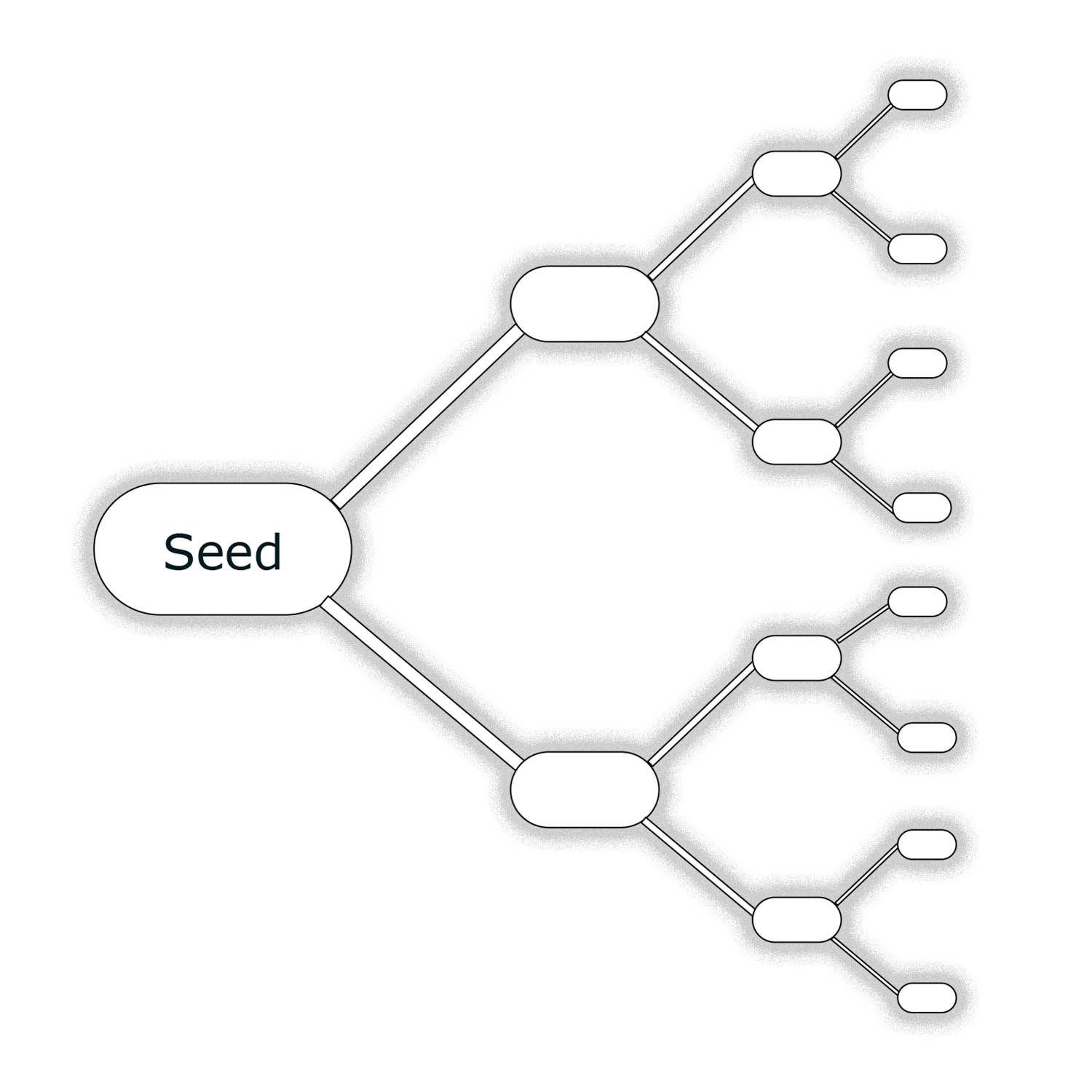

Hierarchical Deterministic Wallets. Hierarchical deterministic wallets are structured as a tree of key pairs. A single master key is stored at the root, and new child keys are derived from a unique derivation path. Each path of the HD tree can be shared without exposing the complete tree.

| HD Tree |

|---|

|

| A tree of HD keypairs. Each branch represents a unique derivation path. |

For cryptocurrency wallets, each blockchain has a unique derivation path. The derivation path contains directions to a key’s location within the tree structure.

HD wallets provide several benefits. For example, HD Wallets permit an online shop to accept payments at a new address for each order without giving the server access to the corresponding private keys (required for spending the received funds).

5. Secure Wallet Origin Distribution (SWORD)

To secure ownership and privacy across the web, we need a better way to protect asymmetric keys. Fortunately, threshold cryptography provides a neat solution.

As a quick reminder, threshold cryptography protects information by splitting pieces of a secret between groups.7

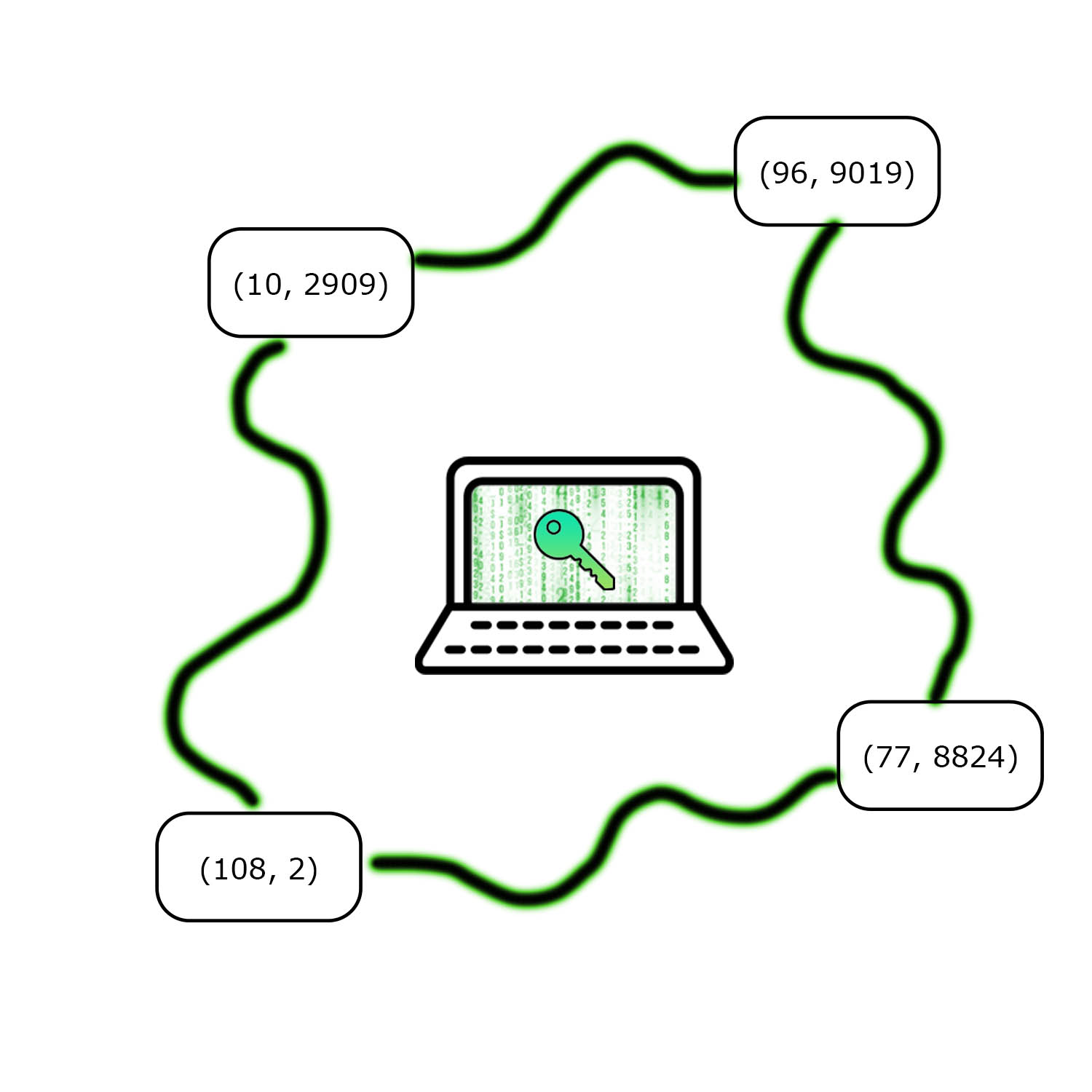

Instead of relying on a smart contract with trusted guardians, SWORD distributes shares of an encryption key to a group of shareholders; k of n shares are required to reconstruct the original secret.8 The encryption key creates an encrypted version of the wallet. Whenever a user wants to regain access to their wallet, the shares are reassembled, and the wallet is decrypted.

| SWORD Shareholders |

|---|

|

| Kryptik key management splits a secret encryption key among n shareholders. Each share is represented as a coordinate point. K shares are required to recover the original secret. |

The Kryptik key management has a number of positive properties:

- Network Agnostic. Kryptik is network agnostic. Use any blockchain you want.

- Quick recovery. Account recovery takes seconds instead of days. Just log in like you would for any other app. Creating a new shareholder is also fast.

- Multi-factor Authentication. Verify ownership of your account with a combination of any standard authentication scheme like 2fa.

- Predictable Fees. Transaction verification logic is unmodified and the cost can be hard coded by applications.

- No setup cost. No smart contracts need to be created or paid for.

In short, Kryptik key management addresses the complexity, fees, and time delay of smart contract wallets. Furthermore, shareholders can be used for wallet recovery and authentication.

6. Challenges

While secret sharing improves the security of online wallets, there are several challenges. Each challenge presents tradeoffs between security and ease of use that must be addressed by Kryptik.

Ciphertext Storage. Ciphertext storage presents a tradeoff between security and convenience. By keeping ciphertext on the original device, shareholders function as gatekeepers, releasing shares when specific criteria have been met: for example, when a login link has been clicked, or security questions have been answered. Since the wallet owner is the only one with access to the ciphertext, shareholder collusion will not compromise the wallet. The secret encryption key may be recovered, but decrypting the wallet is impossible without the corresponding ciphertext (held in local storage).

Local Storage Drawback

Wallet recovery is no longer an option if the user's device is lost or stolen.

Cloud storage removes the user's device as a single point of failure. Anyone who has access to the remote database has access to the ciphertext. If the database is a blockchain like Ethereum, then the wallet ciphertext is public and viewable by anyone. In this case, shareholder collusion would compromise the wallet.

Cloud Storage Drawback

K of n shareholders can collude and decipher the public ciphertext.

Permissioned databases like AWS provide an alternative to public storage on a blockchain. Users can upload a copy of the ciphertext to a cloud provider like AWS and benefit from server-side access control. However, each shareholder would need access to the database to retain the benefits of cloud recovery. At this point, the security assumptions become identical to the public model.

| Local Storage | Cloud Storage |

|---|---|

| Keeps ciphertext on the same device that generates shares. | Keeps ciphertext on a remote database like AWS or Ethereum. |

| A single copy. Easy to lose. | Multiple copies. Hard to lose. |

| Recovery requires possession of the device. | Recovery requires access to the database. |

Denial of shares. Shareholders may refuse to respond. K of N shares are required to reconstruct the original secret. If more than M-K shareholders refuse to respond, there is no way to reconstruct the original secret.

The wallet owner can keep k shares to avoid the ‘denial of shares’ attack, but this creates a single point of failure. Shares can be stored on separate devices, but there is still the underlying concern of a single person owning k shares.

False shares. Malicious shareholders may cheat and submit incorrect shares. Cheating does not compromise wallet security, but it does impair recovery. A single incorrect share is enough to invalidate reconstruction.

In the case of a cheater, the recovery protocol can cycle through k of m submitted shares to obtain a valid subset. Recovery is possible as long as k of m submitted shares are honest.

Kryptik Implementation Details

Distributed key management is a general tool for sharing secrets online. While several secret sharing implementations— such as SLIP 044— have been proposed, each implementation suffers from various drawbacks that limit usability. SWORD uses encryption and authentication to achieve a better balance of security and usability. Specific design decisions made by SWORD are discussed below.

Optimal threshold. SWORD requires two-of-three shares for wallet recovery. An external database manages one share; separate user devices store the remaining shares. The two-of-three threshold provides fault tolerance in case one of the shareholders becomes unresponsive.

| Shareholder | Purpose | Holds Ciphertext? |

|---|---|---|

| Primary User Device | Distributes shares and initiates transactions. | Yes |

| Secondary User Device | Used for wallet recovery if the external database refuses to respond. | Yes |

| External Database | Authenticates share requests. Release share if the request is authorized. | No |

Wallet Storage. Local wallets are held in a software vault. Vaults are locked by default and can only be unlocked with a valid set of shares. The standard vault interface is shown below.

interface VaultContents {

// ciphertext of encrypted seedloop

seedloopSerlializedCipher: string;

// version: default is 0

vaultVersion: number;

// share of the encryption key

localShare: string;

// timestamps stored as...

// number of milliseconds since the epoch

lastUnlockTime: number;

createdTime: number;

// user id generated by wallet app

uid: string;

// if unlock correct, should read "valid"

check: string;

}

Share Generation. New vaults are encrypted with a 256-bit encryption key, which is then split into m shares. Shares are created using shamir secret sharing configured with a finite field in Gf(28) and 128 bits of padding. Each shareholder receives a single share.

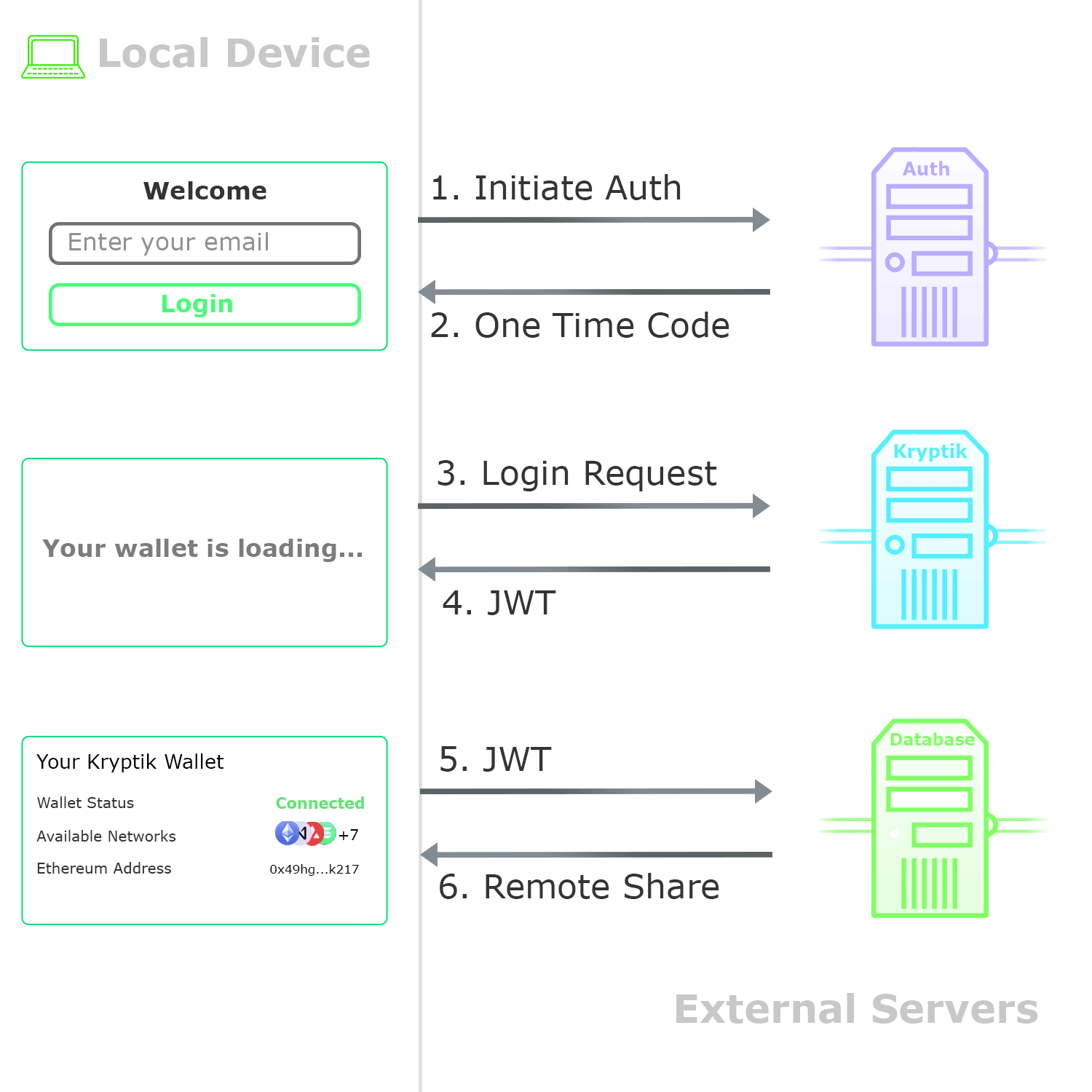

External Authentication. An external authentication provider generates a one-time code, which is shared via email. After validation, the code is exchanged with the database for an access token, and the user session begins. No passwords are required.

| Kryptik Authentication Flow |

|---|

|

| The passwordless authentication flow. A one-time code is sent via email. After validation, the user can access the server’s secret share. |

Recovery. When a new user session begins, SWORD retrieves the database share and combines it locally to recover the original encryption secret. The wallet is then decrypted and made available for use. This arrangement results in a strong security scheme, where an attacker must compromise two of three systems to obtain a user’s private seed.

If the database is unresponsive, a share can be retrieved from the user’s secondary device via a QR code.

Synchronization. Initial share distribution requires an exchange of credentials between the user’s primary and secondary devices. The user’s primary device displays two QR codes: one code for the local shamir share and one code for the wallet ciphertext. Both codes are protected from prying eyes by a temporary encryption key only authenticated users can access.

After the QR codes have been scanned and decrypted, an identical vault (with a unique shamir share) is created on the secondary device.

Conclusion

SWORD uses shamir secret sharing and symmetric encryption to improve wallet security. When implemented in software, SWORD provides users with a simple wallet experience that does not require passwords or smart contracts.

Footnotes

-

Charoenwong, Ben and Bernardi, Mario, A Decade of Cryptocurrency ‘Hacks’: 2011 – 2021 (October 1, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3944435 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3944435 ↩

-

Argent (2020, October 8). Guardian Approvals. Retrieved January 4, 2023, from https://support.argent.xyz/hc/en-us/articles/360008828238-Guardian-approvals-needed- ↩

-

Ethereum (2021, September 29). EIP-4337: Account Abstraction Using Alt Mempool. Ethereum.org. Retrieved October 7, 2022, from https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-4337 ↩

-

Canetti, R., Gennaro, R., Goldfeder, S., Makriyannis, N., & Peled, U. (2020). UC Non-Interactive, Proactive, Threshold ECDSA with Identifiable Aborts. In CCS 2020 - Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 1769-1787). (Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372297.3423367 ↩

-

ZenGo (2018, June 28). Multi-party ECDSA. Github. Retrieved January 11, 2023, from https://github.com/ZenGo-X/multi-party-ecdsa ↩

-

BitcoinWiki (2019, May 23). Deterministic Walet. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://en.bitcoinwiki.org/wiki/Deterministic_wallet ↩

-

Alfredo De Santis, Yvo Desmedt, Yair Frankel, Moti Yung: How to share a function securely. STOC 1994: 522-533 ↩

-

Adi Shamir. 1979. How to share a secret. Commun. ACM 22, 11 (Nov. 1979), 612–613. https://doi.org/10.1145/359168.359176 ↩

Keep Reading

Explore more ideas from the frontier of online ownership.